Journées d’études "Contemporary Ruins/Les ruines contemporaines"

« Les Ruines contemporaines »

9 et 10 décembre 2021

Université de Strasbourg

Manifestation organisée avec le soutien de la MISHA, l'UR SEARCH, l'UR Mondes germaniques et nord-européens, le CHER, la HEAR et l'IUF.

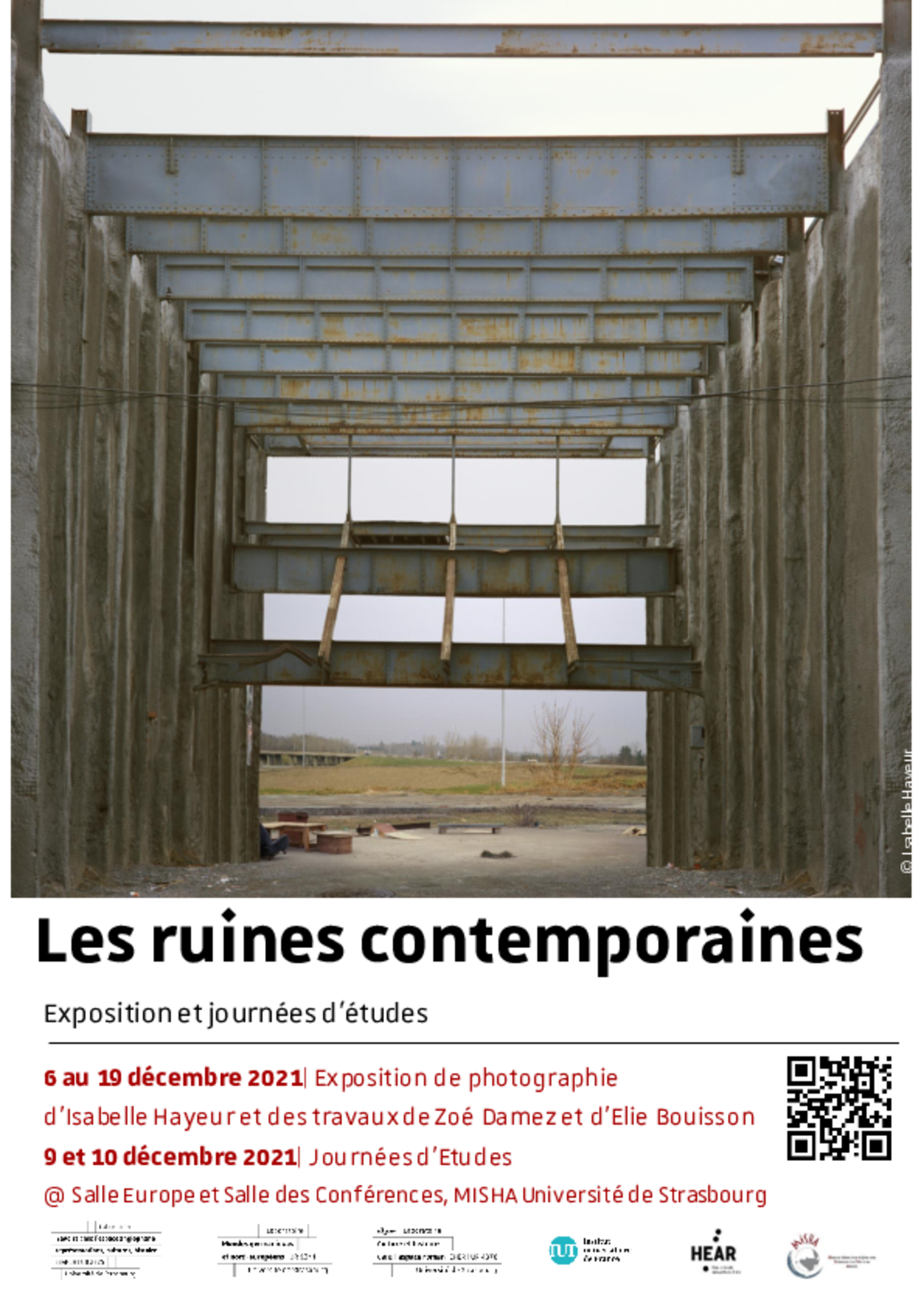

Invités d'honneur confirmés: Isabelle Hayeur (photographe, Canada) et Miles Orvell (américaniste et historien de la photographie, Temple University, Philadelphie)

Comité d'organisation: Emmanuel Béhague, Gwen Cressman, Hélène Ibata, Monica Manolescu

L’association du paysage et de la ruine est aussi ancienne que l’idée de paysage elle-même. Tantôt source de nostalgie, tantôt source de plaisir esthétique et de créativité, la ruine a longtemps été associée à une idée d’équilibre entre nature et culture (Simmel), ainsi qu’aux cycles de l’histoire. Ses transformations esthétiques au cours des siècles ont reflété les tensions entre la temporalité humaine et celle du monde naturel, tout en proposant des résolutions changeantes à ces dernières. Tandis que la mode du pittoresque permit pendant de nombreuses décennies d’intégrer les vestiges des civilisations disparues dans un cadre naturel harmonieux, en en faisant un motif visuel agréable bien que teinté de nostalgie, et que les romantiques virent dans le motif du fragment un moyen d’articuler forces destructrices et forces créatrices, le potentiel esthétique de la ruine et la fascination qu’elle continue d’exercer deviennent aujourd’hui davantage problématiques. Cela est d’autant plus le cas que le motif de la destruction ne s’inscrit plus uniquement dans les constructions humaines, mais dans les milieux naturels eux-mêmes, ruinés par l’action industrielle, incapables de proposer une image de permanence en contrepoint à l’histoire de l’humanité ou de nous promettre une reconquête végétale comme c’était le cas dans la ruine pittoresque. Devant la difficulté d’un jeu esthétique avec ces vestiges du monde naturel, de nouvelles modalités de représentation voient le jour. Tandis que certains artistes font le choix de confronter le spectateur à un monde défiguré, irrémédiablement blessé ou insidieusement pollué (on pense aux britanniques Keith Arnatt, Tacita Dean, Jane et Louise Wilson, à la canadienne Isabelle Hayeur, aux allemands Jordi Antonia Schlösser et Thomas Struth, et à l’autrichienne Lois Hechenblaikner), d’autres s’interrogent sur la possibilité d’un regard esthétisant sur les mutations paysagères de l’ère industrielle (les travaux du britannique Darren Almond, ou des photographes américains Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, ou encore Richard Misrach, s’intéressent ainsi aux inscriptions de l’activité industrielle, minière et pétrolière).

Nos deux journées d’études ont pour objectif d’examiner la signification de la ruine dans la création artistique contemporaine, tout en s’interrogeant sur la façon dont la pensée du paysage peut évoluer pour intégrer la figure de la destruction environnementale. L’artiste peut-il/elle comme par le passé se saisir des ruines du monde pour s’y ressourcer, pour y trouver les fragments de nouvelles compositions, ou doit-il/elle inévitablement nous rappeler à la réalité en nous confrontant à une nature meurtrie, envahie par les signes d’une présence humaine destructrice ? Comment la pensée esthétique du paysage peut-elle articuler ou être associée à une réflexion plus éthique sur la responsabilité de l’humanité dans la crise environnementale actuelle ? Telles seront les questions évoquées lors de ces journées d’études.

Les réflexions pourront porter sur les ruines industrielles et minières, les milieux naturels dégradés, le Land Art, ou encore l’art in situ et son utilisation d’espaces en friche ou en réhabilitation, conçus en tant que pratiques ou vus au travers de supports artistiques comme la photographie, la vidéo ou la peinture. Elles pourront également s’intéresser à la pensée du paysage, dans sa dimension esthétique, mais aussi géographique ou politique.

Références

Dillon, B. (ed.) (2011): Ruins: Documents of Contemporary Art. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Dillon, B. (2014): Ruin Lust. London: Tate Gallery Publishing.

Hell, J. and A. Schönle (eds.) (2009): Ruins of Modernity. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Macaulay, R. (1953): The Pleasure of Ruins. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Makarius, M. (2011): Ruines. Paris: Flammarion.

Orvell, Miles (2021): Empire of Ruins. American Culture, Photography, and the Spectacle of Destruction. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Simmel, G. ([1911] 1958): “The Ruin”, in “Two Essays”, The Hudson Review, vol. 11:3/Autumn 1958, pp. 371-385.

Stewart, S. (2020): The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

“Contemporary Ruins”

December 9-10, 2021

University of Strasbourg

Organized with the support of MISHA, UR SEARCH, UR Mondes germaniques et nord-européens, CHER, HEAR and IUF.

Confirmed keynote speakers: Isabelle Hayeur (photographer, Canada) and Miles Orvell (professor of American studies and historian of photography, Temple University, Philadelphia)

Organizers: Emmanuel Béhague, Gwen Cressman, Hélène Ibata, Monica Manolescu

The combination of landscape and ruin is as old as the idea of landscape itself. At times a source of nostalgia, at other times a source of aesthetic pleasure and creativity, the ruin has long been associated with the idea of balance between nature and culture (Simmel), as well as with the cycles of history. Its aesthetic transformations through time have reflected the tensions between human temporalities and those of the natural world, while offering changing responses to the latter. In the late eighteenth century, the fashion for the picturesque made it possible to blend the vestiges of past civilisations within harmonious natural settings, using them as agreeable visual motifs – albeit filled with nostalgia. Romantic artists saw the motif of the fragment as a means to articulate destructive and creative forces. Today, however, the aesthetic value of the ruin, and the fascination it continues to exert, have become more problematic. This is all the more the case as the motif of destruction is no longer to be found exclusively in human constructions, but in natural environments themselves, ruined by industrial action, unable to offer an image of permanence as a counterpoint to the history of humanity or of promising the return to a natural state as was the case with the picturesque ruin. As the vestiges of the natural world resist the possibility of aesthetic play, new modalities of representation are emerging. While some artists choose to confront the viewer with an irreparably damaged or insidiously polluted world (British artists Keith Arnatt, Tacita Dean, Jane and Louise Wilson, Canadian photographer Isabelle Hayeur, as well as German artists Jordi Antonia Schlösser and Thomas Struth come to mind), others question the possibility of an aesthetic assessment of the landscape mutations of the industrial era (as is the case in the work of British artist Darren Almond, or American photographers Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz and Richard Misrach, who record the lasting inscriptions of industrial, mining and petroleum activities).

Our symposium aims to examine the meaning of ruin in contemporary art, while questioning the possible evolution of aesthetic reflection about landscape in order to encompass environmental destruction. Can the artist, as in the past, find inspiration in the ruins of the world, and see in them the fragments of new compositions, or should they inevitably remind us of reality by confronting us with a bruised natural world, pervaded by the signs of a destructive human presence? How can aesthetic reflection about landscape articulate or be associated with a more ethical assessment of humanity’s responsibility in the current environmental crisis? These are the questions that will be explored during this symposium.

Presentations can focus on industrial and mining ruins, degraded natural environments, Land Art, or site-specific art and its use of wastelands or transitional territories, conceived as practices or seen through artistic media such as photography, painting or video. They may also examine the changing theory of landscape, in its aesthetic, but also geographical or political dimension.

References

Dillon, B. (ed.) (2011): Ruins: Documents of Contemporary Art. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Dillon, B. (2014): Ruin Lust. London: Tate Gallery Publishing.

Hell, J. and A. Schönle (eds.) (2009): Ruins of Modernity. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Macaulay, R. (1953): The Pleasure of Ruins. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Makarius, M. (2011): Ruines. Paris: Flammarion.

Orvell, Miles (2021): Empire of Ruins. American Culture, Photography, and the Spectacle of Destruction, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Simmel, G. ([1911] 1958): “The Ruin”, in “Two Essays”, The Hudson Review, vol. 11:3/Autumn 1958, pp. 371-385.

Stewart, S. (2020): The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.